How the City of Fort Worth Saved Millions

In the United States, prescription drug spending in 2020 reached $358.7 billion; $3.5 billion is estimated to be fraud, waste, and abuse.

The City of Fort Worth, Texas — the 12th largest city in the U.S. and the 5th largest in the state — presents a textbook case study for the pervasiveness of pharmacy fraud hidden in healthcare claims and the action required to combat the ever-evolving abuse.

In 2017, the City was $15.2 million overbudget on employee healthcare spending. With just shy of 7,000 employees, benefit costs have been a significant portion of the City’s budget. To address the rising costs, officials took innovative steps to reduce spending including working with an accountable care organization (ACO), opening clinics exclusively for city employees, and bringing in a third-party to analyze and review its employee healthcare claims for fraud, waste, and abuse. By 2019, the City saw nearly $11 million in healthcare savings due to these combined efforts.

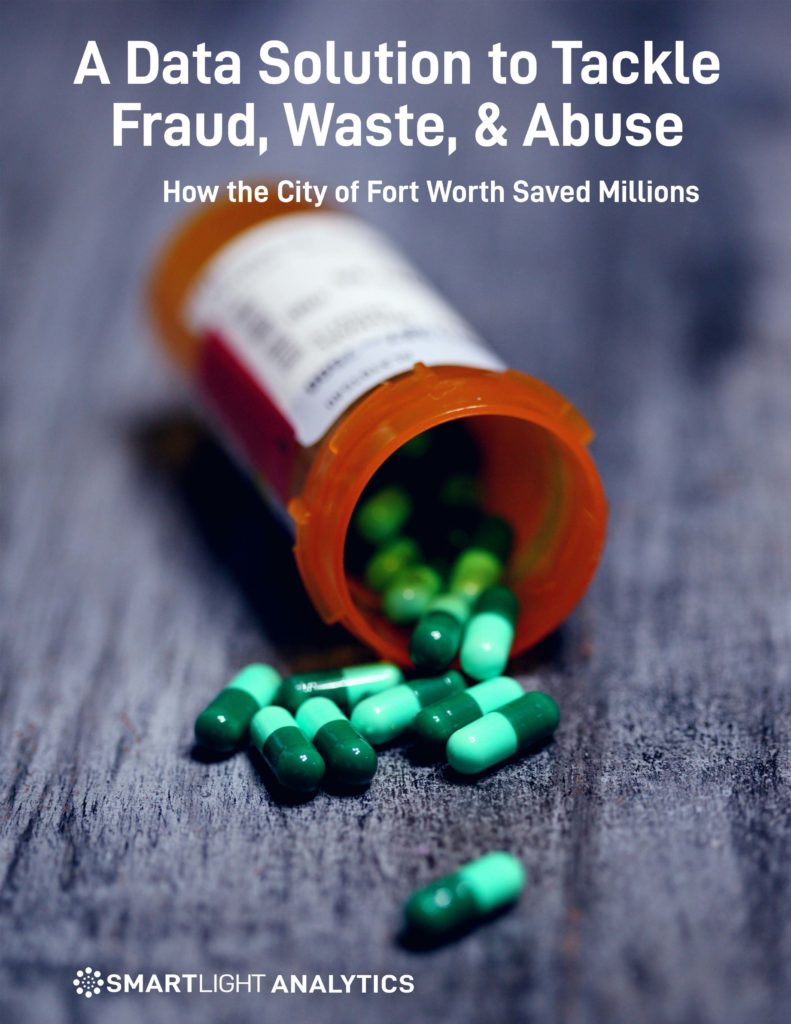

Like most municipalities and businesses, the City continues to battle the rising cost of healthcare, and in 2020-2021 found fraud was beginning to eat away at its savings. Working with new focus on actively reviewing employee healthcare claims with the help of an independent partner, the City began to identify and remove all types of fraud, waste, and abuse. The partnership has produced more than $3.5 million in realized savings back to the Plan to date*. Focus on eliminating the identified fraudulent and abusive pharmacy spending was the next step.

FOCUS ON DATA

Nathan Gregory, HR Director for the City of Fort Worth, was aware of pharmacy fraud and knew situations existed where unscrupulous actors obtained member healthcare information and used it to bill health plans for non-existent or fraudulent prescriptions. However, he was not aware to what extent it existed within the City’s health plan. A focused look at the data provided the insight.

Asha George is the CEO and co-founder of SmartLight Analytics, which partners with Fort Worth to analyze claims for wasteful spending. Her team began to see patterns in Fort Worth’s healthcare claims data indicating suspect billing of likely fake prescriptions.

“The patterns indicating abusive billing were clear. Members were being prescribed broadly available creams and ointments by physicians that they hadn’t seen, and the prescriptions were filled at pharmacies hundreds of miles away from their home,” George said. Working with Fort Worth’s pharmacy benefits manager (PBM), a plan was developed to suspend payments to pharmacies where clear abusive patterns were noted in the data while investigations were pursued. Using this process, the City has now suspended claims to 24 suspect pharmacies preventing an estimated $1.7 million in fraudulent payments. It should be noted that the findings and actions were not disruptive for Fort Worth’s members. To date, not one member complaint has been received, further confirming the members were not aware these prescriptions were being filled under their pharmacy benefits.

“Whenever we find waste, fraud, or abuse for obvious reasons, we want to stop that as quickly as possible. Everything we do within our health fund, we do with an awareness that ultimately, we are dealing with taxpayer funds. It’s our responsibility to provide good benefits to our employees but also in a sustainable manner so that our health plan is sustainable in the long-term,” said Fort Worth’s Nathan Gregory.

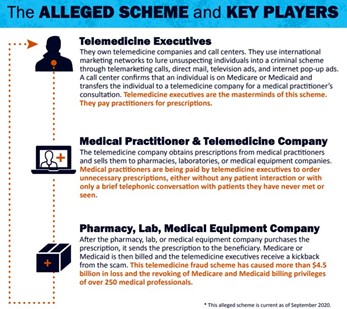

One example of a pharmacy fraud scheme operate is abusive telemarketing companies that generate pre-populated prescription forms for drugs, dosages, and quantities set regardless of the patient or condition. This results in each patient receiving identical fills of medically unnecessary medications, regardless of their ages, medical histories, or other individual factors. The prescriptions are then sent to a medical practitioner within the telemarketing companies’ “network” for authorization. This practitioner is typically not the member’s PCP or any other physician treating the member. Once the prescription is signed, it is sent to a partner pharmacy that is cooperating in the scheme, which is typically not the member’s regular pharmacy.

EXAMPLES OF PHARMACY FRAUD FINDINGS IN FORT WORTH’S DATA

PHARMACY EXAMPLE #1

Since October 2020, a retail pharmacy located in North Texas had billed the City for claims later confirmed to be associated with a fraud, waste, and abuse (FWA) telemarketing scheme. The owners of this pharmacy were associated with owners and pharmacists of other businesses in Texas known to participate in various pharmacy FWA schemes. This pharmacy was referred to the PBM for pharmacy exclusion (for City of Fort Worth members only) for engaging in a telemarketing/solicitation scheme, where prescriptions were obtained and filled fraudulently.

IDENTIFIED ISSUE

All prescriptions submitted by this pharmacy were made up of one or more of the same three high-cost medications billed with identical dosage and quantities, irrespective of the patients varying ages and medical diagnoses – 60 tablets of Nicazyme, a dietary supplement; 135 grams of Zonalon, which is the brand name for doxepin 5% cream, a topical nerve pain medication; and 946 milliliters of Naprosyn, a liquid form naproxen. The same two prescribers wrote the prescriptions for these creams and supplements. One prescriber practiced at an address over 300 miles from members’ homes; and the second prescriber practiced over 250 miles away from his patients. Based on a review of the medical claims, there was no indication any of these members had been seen by the physicians who wrote their prescriptions nor that these members have been legitimately diagnosed with a medical condition that would necessitate the use of the prescribed medications.

SUSPECT PATTERN

• Absence of patient-practitioner relationship – No records showed the member was seen by the physician the pharmacy used to bill the claims.

• Absence of valid medical diagnosis – Little to no records showed the member was diagnosed, neither by the physician the pharmacy billed nor any other physician, with a medical condition that would necessitate the prescriptions billed by the pharmacy.

• Patient’s preferred pharmacy – This pharmacy was determined not to be the members’ regular pharmacy. Members filled all other medications from pharmacies near their home. Only the specific high-cost creams and supplements were filled at the suspect pharmacy.

IDENTIFIED COST SAVINGS TO THE CITY OF FORT WORTH:

$171,828

PHARMACY EXAMPLE #2:

A 40-year-old male employee was referred for opioid management for filling multiple controlled substances from multiple pharmacies prescribed by two suspect providers.

IDENTIFIED ISSUE

This member’s opioid prescriptions were consistently filled at different pharmacies from those where his maintenance medications were filled. In addition to multiple opioids, the member also received butalbital/acetaminophen/

caffeine/codeine combination monthly along with several anti-depressants. Butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine is a combination medicine used to treat tension headaches and was being prescribed by two different providers. The combination, long duration (over 3 years), and high quantities of the controlled drugs this patient received warranted a need for case management. There was also a possiblity that this member might be illegally selling these medications.

SUSPECT PATTERN

• Member utilized multiple pharmacies to fill controlled scripts.

• Both physicians at the prescribing office had a history of suspect billing.

• Member received 120 tabs of hydrocodone each month since 2018.

• Additionally, the member continued to receive 30-60 tabs of butalbital/acetaminophen/caffeine/codeine monthly. This medication is not recommended for long-term daily use as it could be abusable and habit-forming.

IDENTIFIED COST SAVINGS TO THE CITY OF FORT WORTH:

$16,760

PHARMACY EXAMPLE #3:

A family-owned retail pharmacy that purports to provide personalized attention and care to each of its clients was identified for engaging in billing indicative of a known FWA scheme. This pharmacy billed claims for topical ointments for 40 City members; all medications were those typically observed in known patient steering schemes.

IDENTIFIED ISSUE

The pharmacy was referred for potentially steering members to its location specifically to fill high-cost ointments only. The members all appeared to have continuous history of fills for all other medications from nearby pharmacies. This pharmacy did not appear to be the members’ regular pharmacy.

SUSPECT PATTERN

• The targeted pharmacy was located nearly 100 miles from Fort Worth members.

• Other pharmacies billed for the members’ monthly maintenance medications refills.

• This pattern was consistent with prescriptions that had been steered to specific pharmacies with the guarantee of lower patient responsibility.

• Within the scheme, pharmacies used coupons to reduce the patient’s responsibility.

• This pharmacy had been identified and confirmed for suspect billing in other client’s data.

Steering patients is illegal in most states due to specific statues that require prescriptions be sent to the pharmacy of patient’s choice, and no activity, by either pharmacy, provider, or PBM, can hinder that. Some pharmacies that engage in patient steerage also waive required copays to induce additional fills. Steering may indicate a violation of Stark or Anti-kickback laws.

IDENTIFIED COST SAVINGS TO THE CITY OF FORT WORTH:

$36,280

FOCUS ON ACTION

The targeted pharmacy exclusions have been in effect for over a year now. Throughout this time period, the City has not received any “noise” from employees regarding denied prescriptions — an indication that members were not aware of the fraudulent prescriptions being paid for through their benefit plan. The City and its FWA partner proceed extremely cautiously in making each referral into the exclusion program to ensure that valid prescription fills are not disrupted.

“We only recommend stopping claim payment in situations where it’s obvious it’s fraudulent,” Gregory said. “The healthcare system is still like the Wild West at times. As much as the government has tried to put regulations in place, there are still multiple loopholes for providers and, in this case, pharmacies to fraudulently work the system. We believe this (continual claims review for fraud, waste, and abuse) is a permanent part of how we have to operate,” Gregory said.

“We have always known for years there have been reports of fraud, waste, and abuse in the

healthcare system. One out of every three dollars is the typical statistic given,” Gregory said. “These consistent reviews give us a way to at least feel like we are doing what we can to combat FWA.”

Conducting proactive claim reviews monthly provides a more in-depth level of insight and the ability to act quickly to stop wasteful spend. When pharmacy and medical data are combined, a complete picture can more clearly identify suspected cases like the examples above. This partnership also works to combat the ever-evolving abusive schemes. As plan sponsors implement tighter controls on one drug or pharmacy, as the City of Fort Worth did, the fraud scheme moves to the next drug or newer pharmacy. In the case of Fort Worth, two new pharmacies showed up in its claims in May 2021 and were immediately identified as problematic and within two weeks, payments from Fort Worth’s health plan to these pharmacies were suspended, saving thousands of dollars in unauthorized prescriptions. It is an unusually quick response in the healthcare claims space and an example of employer, payor and analysts working collaboratively to stop obvious abuse.

How does a scheme operate?

• One telemarketing scheme begins with members receiving unsolicited phone calls inquiring if they have pain or other ailments.

• Pre-filled prescription forms are generated over the phone.

• The prescriptions are sent to willing prescribers (doctors who agree to participate in the scheme, usually for a fee per prescription) for signature.

• The ”authorized” prescriptions are sent to the targeted pharmacies that are involved in the scheme to fill through insurance.

SUMMARY

Large employers with self-funded healthcare plans are susceptible to pharmacy fraud and abuse that can amount to hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars in waste each year. The fraudulent practices come from both members abusing prescribed substances and, in large part, from pharmacy schemes carried out under the radar. Finding and stopping such fraud and abuse takes regular proactive claim reviews to provide a deep level of insight and the ability to act quickly to stop wasteful spending. It is important to combine pharmacy and medical data to compose a complete picture to identify suspected cases and to combat the ever-evolving abusive schemes.

KEY TAKEAWAY

The City of Fort Worth has now suspended 24 suspect pharmacies from billing its plan, preventing $1.7 million in fraudulent payments to date, without member disruption. A total of $2.3 million in savings have been identified.

MORE INFORMATION ON PHARMACY FRAUD

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/pharmacy-owner-pleads-guilty-65-million-health-care-fraud-schemes

https://www.statista.com/statistics/184914/prescription-drug-expenditures-in-the-us-since-1960/

https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NHE-Fact-Sheet

https://www.amcp.org/policy-advocacy/policy-advocacy-focus-areas/where-we-stand-position-statements/fraud-waste-and-abuse-prescription-drug-benefits

https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/feds-recover-1-8b-from-false-claims-act-cases-2020

https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/four-men-and-seven-companies-indicted-billion-dollar-telemedicine-fraud-conspiracy

* As of May 2022

Would you like a copy of this paper? Click here.